Princeton's Elizabeth Ellis, a historian and citizen of the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, is a key player in an exhibition at the Palace of Versailles that brings to light the little-known diplomatic history of French-Native alliances. It opens on Nov. 25.

Elizabeth Ellis

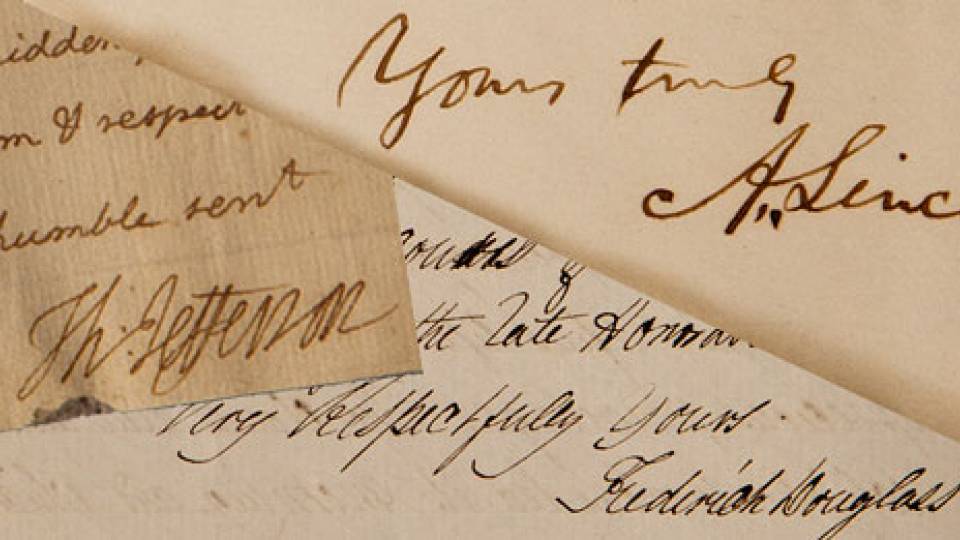

In 1725, five Native American diplomats from the Otoe, Osage, Missouria and Illinois (Peoria) Nations of the Mississippi Valley crossed the Atlantic to be received at the French court of King Louis XV at the Palace of Versailles.

Their visit recognized the alliance between France and the Native American nations.

Three hundred years later, a museum exhibit at Versailles will commemorate the event, showcasing research by Princeton historian Elizabeth Ellis, a member of the exhibit's scientific committee.

Ellis, associate professor of history, is a citizen of the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, one of six Native nations who partnered with French museum curators on the exhibit, “1725: Native American Allies at the Court of Louis XV.” She provided historical and cultural expertise on behalf of both the Peoria Nation and the University.

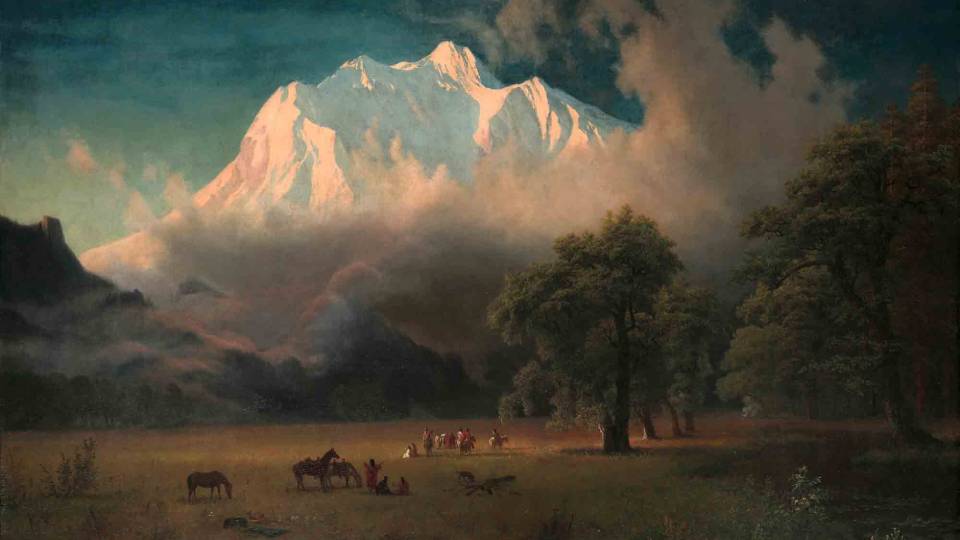

The exhibit features 17th- and 18th-century Native American artifacts and artwork acquired by French colonists and uses them to explore the dynamics of the international alliances between France and its Native allies — which helped establish the French influence in Louisiana that endures today.

It also recalls little-known details from the 1725 diplomatic mission to Versailles. The Indigenous delegation toured the French palace, delivered speeches of allegiance to the royal court, and hunted alongside King Louis XV at the Château de Fontainebleau.

Exquisite Native American deer hide robes from the French government’s collections that showcase Indigenous artistic traditions and stories are one of the exhibit’s marquee attractions. During the 1700s, these minohsayaki robes were gifted or traded during French-Native exchanges like the meeting at Versailles.

The painted hide robes are “one of the few sets of surviving material culture items” from that diplomatic era, Ellis said. They demonstrate Indigenous artists’ distinctive aesthetics — Peoria robes, for instance, use an angular, minimalist style — along with documenting “what they thought was important to inscribe, record and note” for diplomatic gifts and trade.

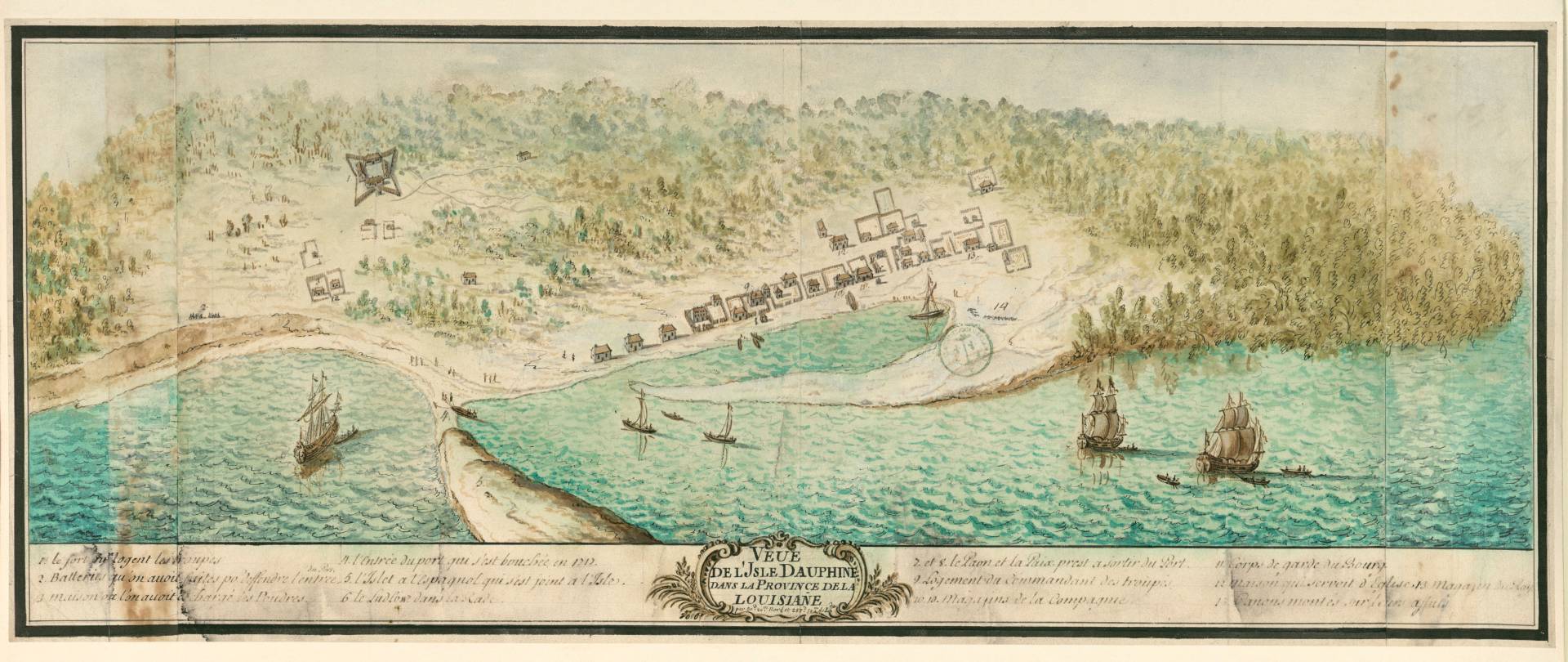

Other items in the show include a chief’s headdress, colonial maps of Louisiana, and a feathered peace pipe with a matching painted hide robe.

The exhibit opens Nov. 25 — the anniversary of the historical meeting — and runs until May 3, 2026.

Native American deer hide robes from the French government’s collections that showcase Indigenous artistic traditions and stories are one of the exhibit’s marquee attractions. During the 1700s, these minohsayaki robes were gifted or traded during French-Native exchanges like the meeting at Versailles. The painted hide robes, like the Peoria one pictured, are “one of the few sets of surviving material culture items” from that diplomatic era, said Ellis.

A common history, explored as colleagues

An 18th-century feather bonnet headdress featured in the exhibit.

“Native nations have been dealing as nations with foreign powers for hundreds of years,” said Ellis, a historian of Native and early America who has taught at Princeton since 2023. “This is well before the creation of the United States.”

The exhibit at Versailles and an associated academic symposium at the Paris museum Musée du Quai Branly (MQB) will bring new details of that history to light and offer a chance “to reflect on this deep historical connection between our nations,” she said.

Mounting the exhibit at the glittery French landmark underscores a close and ongoing collaboration between France and Indigenous communities to explore their common history.

“The relations that we study in the past are in dialogue with the relations that we are building in the present,” said Paz Núñez-Regueiro, head curator of the Americas Collections at MQB and co-curator of the exhibit.

In addition to MQB, Versailles, the Peoria Tribe and Princeton, collaborators for the exhibit include the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the Quapaw Nation, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, the Osage Nation and the Otoe–Missouria Tribe of Indians in association with MQB's Royal Collections of North America Project, which aims to foster an interchange of Indigenous and academic knowledge.

“The field of Native history, and Native American studies more specifically, has really pushed scholars to work towards working with communities, rather than on communities — to move away from that really extractive model of research,” said Ellis. “That's something that has transformed, I think, the way we understand these histories, the significance of stories like these, these kinds of encounters.”

“It's also been really wonderful to be here at Princeton and be in the position where I have been supported by my University in pursuing what we could think of as public history research — or tribally engaged research, collaborative research — that involves tribal publics, European publics and American publics.”

Princeton has strengthened its support of Native American and Indigenous research and scholarship in recent years. In May, the University announced that a new minor program in Native American and Indigenous studies will be offered through the Effron Center for the Study of America at the start of the 2026–27 academic year.

Prelude to the Versailles exhibit

Shared research interests in minohsayaki and historical relationships among MQB, Versailles, and the Miami, Peoria, Quapaw and Choctaw Tribes sparked the idea several years ago for the tricentenary exhibit at Versailles. Ellis had visited MQB’s collections in 2022 with researchers from the Miami Nation of Indiana as part of University of Illinois history professor Robert Morrissey’s “Reclaiming Stories Project.” This year’s exhibit and symposium grew from there.

Ellis hopes more museums will establish partnerships like MQB's to engage experts from living Indigenous communities and expand the historic and cultural understanding of their collections.

“It's really, from our end, a project of reclamation. The community's interested in revitalizing hide robe painting and these kinds of storytelling and our understanding of our past," she said. Likewise, MQB is "interested in updating their interpretations of these objects” and gaining “different insights into what the symbols and the process mean.”

Ellis said the project’s “cutting-edge approach to community-engaged and public-facing research” is key to finding new pathways for academics and historians to share their expertise with audiences outside of academia.

It also shows “what the potential of engaging with community can be for the way we understand the past and research the significance of these kinds of shared histories,” she added.

"One of the things that's been really amazing for me is the way that these relationships have begun to gradually open doors to help us figure out what else is in the French national collections, where there are other hidden pieces of our history.”

Simon Dusault de la Grave's "Map of Isle Dauphine in the Province of Louisiana" (1746), also part of the exhibit.